Huck Read online

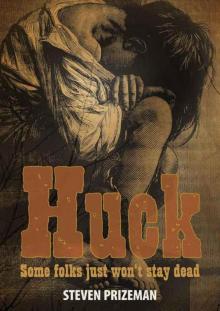

Huck

by Steven Prizeman

Copyright © Steven Prizeman 2011

The right of Steven Prizeman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Contents

Chapter 1: Drownded and grounded

Chapter 2: Loaves and fishes

Chapter 3: Thunderstruck

Chapter 4: Dead. And buried.

Chapter 5: How the cat-skinning begun

Chapter 6: Jim: not a “nigger”

Chapter 7: Whole lot of things happen. Bad, mostly

Chapter 8: His own self!

Chapter 9: Varmints

Chapter 10: Big Missouri

Chapter 11: Sometimes folks get hurt

Chapter 12: Underworld

Chapter 13: Teeth, blood ’n’ water

Chapter 14: Some things end, some don’t

About the Author

Suggestions for Further Reading

Chapter 1: Drownded and grounded

It was when Joe come back from the dead our troubles begun, I reckon. Things was none too cheery ’fore then, of course, what with us thinking him drownded, Tom and me, but… well, it’d’ve been better all round if he’d just stayed dead. Them was the fun times, I’ll allow, when I think what come later. But I’d better back up a pace, I guess, and say how things got started. Was like this:

We was out on the river that night, Tom and Joe and me – headed for Jackson’s Island. Had a mind to be pirates for a time and reckoned that was the place. We was in regular high spirits at the thought, the fighting and booty and all. Reckon they was too high – we warn’t mindful of the river, and the Mississip don’t like that. No, sir – you forget about the Miz, stop payin’ her the respect she’s owed, she’ll remind you what’s due, real fast. Reckon that’s why we run smack into that undertow – it come and grab us like a regular rip and whip us agin a big old log floating nearabouts, right at the corner Joe’s a-standing on. ’Fore we know it, it lifts up and tips us in. Heard Joe scream as I went under – reckon we all screamed; but it’s his voice I ’member.

Tom ’ready has his head ’bove water when I come up. He’s a-coughing and a-spluttering something awful and trying to pull hisself back onto the raft, which is upside-under now and spinning and tossing like a colt, and every time his fingers gets a-holt, the river tugs it away agin and sends it plunging straight back, like to stove his head in if he ain’t careful.

“Where’s Joe?” says I, spitting out a mouthful and treading for all I’m worth (consid’rably more, maybe), but Tom don’t hear me on account of his being in kind of a fix, like I said. Then, ’spite all the splashing that’s a-filling my ears, I hear Joe crying something pitiful and see him yonder, swimming upstream, trying to reach the raft, same as Tom. Only that undertow’s got him and it ain’t letting go till he hollers “nuff”. It’s a-pulling him this way and that, and the raft and the log are whipping all around – Joe stuck in the middle.

“Oh, Lord!” says I. “If you’ve a mind to help us sinners, now’s your chance! Don’t reckon you’ll get another lessen you’re fast.” And I take a deep breath and dive under the raft. When I come up, can’t be more’n a few seconds later, the raft’s spun about a quarter turn; Tom’s got a grip on it now and with his t’other hand he’s holding out an oar to Joe. Joe’s a-reaching and a-clutching, but he ain’t close enough. He looks straight at me – real pale – and says: “Help me, Hucky!” I light out towards him, and I’m hauling some distance and ’most get near enough to put a hand on his shoulder, and he says “Help me, Hucky, and I’ll…” when up jumps that log agin and hits him smack in the chest, knocks the wind clean out. It don’t handle me none too kindly, neither – lams me in the side ’fore shivering the oar, half of which jumps out the river and cracks me a good ’un on the cheek, all sharps and splinters. When I look back at Joe, he’s tumbling away downriver like he’s no more’n a feather. I see his mouth open and close a couple times ’fore he goes under; if he said anything I didn’t hear it.

I look over at Tom, and he’s a-staring after Joe too, a real pained look on his face. I can tell he don’t want another go at that raft, no more’n me, what with it still bucking like nobody’s business, so we both kick ourselves away and just watch it slide after Joe, turning in toward the Illinois side and looking as if it’ll hit the bank a couple of mile down. I see Tom ain’t swimming too well, which is mighty unusual for Tom.

“Cheer up, Tom,” says I. “It’s only a quarter mile or so to the island. If we swim over thataways, all we’ve got to do is let the current carry us down.”

“I can’t swim another stroke, Hucky,” says Tom, all mournful. “I’ve got the cramp, got it real bad.”

“Why, you ain’t hardly got to swim, Tom,” says I. “Only eighty yards or so, then it’s just floating the rest of the way – and floating’s pie.”

“I can’t,” says Tom. “I’ve lost the rattlesnake rattles off’n my ankle – I felt the string snap.”

This is another bad turn, no doubting, ’cause I know how Tom swears by his rattlers and never would go out deeper’n his waist without making sure they was fixed tight.

“Heck, Tom,” says I. “Why, I ain’t never hardly worn rattlers and I ain’t drownded yet. I ain’t wearing none now and I reckon I could reach Jackson’s Island on my back.” (I had my own ways, of course – better’n rattlers. A feller would have to be awful tired of living to splash about in the Mississip without some kind of charm. Still, I didn’t want to fret Tom none, his position being somewhat vexing.) “Hang onto my shoulder,” says I, getting myself alongside. “Reckon I can paddle well enough for the two of us.”

“Your face is bleeding, Hucky,” says Tom, putting his arm round my neck and helping me kick off as best he can.

“Reckon it is,” says I. “Ain’t hardly had time to notice.”

“I guess Joe’s drownded,” says he, and sighs (though he gets choked off, what with the water slapping in our faces and all). “We’ll never see him again.”

“Reckon not,” says I. “Being drownded drives a whole passel of wedges into a friendship, that’s for sure.”

“Bet his ma’ll be sick she whipped him for hooking that jug of cream,” says Tom.

“Reckon so,” says I. “That’s something, I guess.”

Jackson’s Island was pretty well lit up by the moon that night, so’s I had plenty of light to steer us by. ’Bout a quarter hour later or so we feel the water getting shallower and shallower till we put our feet down on a sandbar, easy as you please. Warn’t nothing to take a few hops and steps from there onto the island proper – though Tom and me was plenty glad to be treading land agin and didn’t dawdle none going ashore.

When we’re out the water we walk separate a while, strolling through the trees, making out we’re looking to catch sight of some bats or owls or what not, till we come to a big old sycamore on the edge of a clearing. It looked like it’d be a pretty fine spot to pitch camp if we still had any gear to pitch, only we didn’t hardly have nothing no more – all our vittels was heading for the Gulf of Mexico and every leaf of smoking tobacco had floated off somewheres, and all my chaws was soaked through. And I’d lost my hat.

I guess Tom was beat, ’cause he stops and turns round and I see his eyes is a-drizzling.

“Reckon we might as well stay here for the night, Huck,” says he.

I just kind of nod.

“Say, Hucky,” says Tom, making his voice kind of breezy. “Reckon that cut on your cheek must sting some – it’s making your eyes water.”

“Reckon so, Tom,” says I. “And your cramp’s gone and cramped up your eyes too – ’cause they’re a-watering something fearful.”

“Ind

eed and ’deed, you’re right there, Hucky,” says Tom. “It’s about the crampingest squeeze I’ve ever had put on my eyes. They’re being cramped fit to bust.”

(Point of fact, what was cramping Tom’s eyes was his being cut up something painful on account of Joe – him being his bosomest pal in the world and all. I warn’t so mean as to let on, though.)

I’m about to sit down ’gainst a log when Tom says: “We’d better say something Huck… for Joe. A prayer, I reckon.”

“All right,” says I. “I guess that’s fitting – but you’d best say it. I don’t know no words, and any case, I figure the Lord was only half listening when I spoke to him not an hour since.”

Tom’s versed in his Bible on account of his having forced hisself to go to Sunday school for months at a stretch – a regular martyr to it, reading and a-praising more’n a body could stand. I reckon if anybody’s put in enough hours to deserve a word with the Lord it’s Tom. (Though sometimes I wonder if the Almighty ain’t got it figured kind of strange to make hisself so available to folks in church on Sundays when they’re all dressed up and ain’t facing no more danger than being sermonised at, but he ain’t got time for a boy that’s drowning and still makes an effort to speak to him special. I know what you’re thinking – “Well he saved you, didn’t he, Hucky?” Reckon not. Reckon that just happened. Joe was a good boy, compared with me – a real parasol of virtue – and he was more in need of help than me. Don’t make sense to think the Lord would’ve helped me and not Joe.)

Tom screws his eyes up tight and puts his hands together and I see his lips move as he works out something solemn and preacher-like, then he launches out in a voice fit for a revival meeting.

“Oh, Lord,” says he. “Take unto thyself our dearly departed brother, Joseph Harper. Forgive his trespasses, ’cause we all go a-trespassing sometimes, truth be told. Round back of the Widow Douglas’s place and Farmer Jones’s orchard, in particular – the slaughterhouse too, sometimes – and all them other places I guess you know about. Joe didn’t mean no harm and never took anything worth much. So, for what he is about to receive, may you, good Lord, make him truly thankful. Amen!”

“Amen, to that,” says I. “That was real pretty, Tom.” Tom’s powerful smart at times, and mighty big with his book learning for a boy that plays so much hookey.

I slept better’n I guessed I would, curled up ’neath that sycamore. I didn’t hardly wake at all during the night, just once when I thought I heard someone calling: “Redhanded… Black Avenger… Terror of the Seas.” Them was the pirate names me and Tom and Joe took ’fore we set sail. I woke up sharpish, shivering with cold and laying in a pool of water that must’ve been seeping out my clothes for hours – should’ve took ’em off, I guess. I listened real keenly, but didn’t hear nothing but the wind in the trees; and Tom was still asleep, so I reckoned I just dreamed it. Few minutes later, I was asleep agin.

Next time I wake, it’s morning. Tom’s still asleep, face buried in his arms, shivering. I just leave him be – reckon that’s best. Sun’s already quite a ways up, and the morning fixing to be hot, with a warm breeze coming over from the Missouri side. This is pretty good news, I can tell you, since my clothes is still so damp they’re wet. I take the whole lot off and hang them up on branches to dry. It’s while I’m doing that I have my first bit of luck of the day. I knew I wouldn’t’ve lost my fishing line – sure nuff it’s still in my pocket, wrapped up tight, the hook snagged in the cloth – but I hadn’t counted on finding a chaw of tobacco and a couple of leaves for smoking crammed down under it. A feller’s pockets can get awful busy at times and I reckon I’d just forgot what was in there. Well, that chaw’s in my mouth smartish and those leaves are stuck on twigs and flapping in the breeze pretty quick too. If I’d had a pipe I’d’ve built a fire right off, dried them out and had me a smoke – but since I didn’t, food seemed the next most needful thing.

I walk back the way we come ashore, the island looking more cheerful in the daylight, what with the woods all streaky with sunshine where it cut its way down through the leaves, slicing up the shadows. Crickets was chirping and birds singing too, like they do, and the heat bringing out the smell of the leaves and flowers and such – better’n the wet, earthy smell I’d had in my nose all night. T’ain’t more’n a quarter hour, I guess, till I’m back looking out over that sandbar and the Mississip washing all around it, thick and brown (though way up in the distance, it looks kind of blue and shiny with the sun skimming off of it and all).

“Now, Huck,” says I to myself (only in my head, of course, there being no other folks around). “Where d’you reckon’s a likely spot to catch you and Tom a bite of breakfast?” I look all along the shore and back agin, then up the length of that sandbar till I see a big old rock ’bout a hundred yards out and just over toward the Illinois side – no more’n a good jump away from the sandbar. “Reckon that’s the spot, Huckleberry, old feller,” says I (silent; like I said). “Why, you’ll hardly even get your feet wet.” (Getting wet ain’t nothing to me most times, specially when I ain’t wearing nothing to get ruined up by it, but I warn’t feeling too keen on swimming just then – on account of having done so much the day before, I guess.)

So I hunt round the bushes a couple of minutes till I find a fat old inch-worm, then walk out along that sandbar, fixing it on my hook as I go (which made him squirm somewhat – though I don’t hardly blame him for that). I’ve just started unwinding the line when I feel a knobbly feeling under my foot. So I look down, and what do I see but a corn cob. Reckon it could only be one of my own that I’d took for making pipes with. “Why ain’t that a stroke, Huckleberry!” says I (up in my head). “It don’t look too beat up or soaked through – if Tom’ll lend me his Barlow it won’t hardly take me any time to carve me a pipe and have a smoke.”

So I pick up that corn cob and carry on unwinding the line, walking out along the sandbar toward the rock all the while. And as I get farther out, and the water gets higher, ’most over my ankles, pulling at my feet as it slides over the bar, I see something stuck in the sand and glinting silver. I stoop over and “Dern!” says I – out loud this time, spite of there being nobody to hear. “Ain’t that something!” (Quiet agin, having recollected myself.) “Here’s you, Hucky, wanting a knife to carve a pipe with, and derned if that ain’t a knife right there, just as if it was awaiting for you.” So I pull it out of the sand and “Dern!” agin, if it ain’t Tom’s Barlow – he must’ve dropped it as we come ashore t’other night. “Why,” says I, “I reckon good luck’s just stacking itself up to say sorry on account of yesterday being none too jolly.” And I fair skip up the rest of that sandbar and leap out to that rock certain of catching ’bout the biggest bass anybody ever seed.

Didn’t reckon it’d be long ’fore the fish started biting and I’d be back in the clearing cooking me and Tom some breakfast – but it don’t follow that a feller’s got to go lazying needless, so I said “Huck,” I said, “I reckon you can catch that fish and carve yourself a pipe at the same time. Take this here end of the line and tie it round your ankle till there’s something to haul in.” Now that’s a pretty good idea, no denying, so I do it just so, then cast that inch-worm (still wriggling something pitiful) out into the Miz, ’bout as far as I can sling him. When he’s sunk out of sight, I just lay back on that rock, rest my ankle on t’other leg’s knee and get comfortable while the sun gets higher like there ain’t no stopping it. Well, I lay into that corn cob with the Barlow and soon I ain’t got no troubles bothering me at all, ’cause there ain’t nothing for taking your mind off of things like carving a pipe (’cept smoking one – and I was fixing on doing that later; a chaw’s only so good). So I’m lying there ’bout as happy as a body can be, and I guess I can’t bottle it up – ’fore I know it I’m whistling Buffalo Gals and flicking my foot to and fro and jerking that fish line hither and yon.

“Huckleberry Finn! Ain’t you ashamed of yourself? Don’t you have no respect?”

&

nbsp; It’s Tom that’s shouting. I turn round sudden, just about startled out my skin, and there he is on the sandbar – either he’s sneaked up on me deliberate or I must’ve been whistling mighty loud, ’cause I didn’t hear nothing till then. I can hear something now all right. Tom’s staring at me through a real mean frown, his face about as much like thunder as a face can get. I look at him kind of puzzled and he says: “How can you sit there whistling like you ain’t got no cares in the world, with Joe not more’n half a day dead and not even buried, nor like to be? Joe was your friend and all, warn’t he? Ain’t you in mourning, Huck? Ain’t you a Christian? Ain’t you been brought up decent?” (Point of fact, I ain’t hardly been brung up at all, as Tom knowed well.)

“’Course Joe was my friend,” says I, standing up to look more respectful. “And I’ve been sorrowful on his account, ’deed I have, Tom. And I reckon I’m as much a Christian as the next feller, ’cause far as I know everybody’s a Christian ain’t they, ’cepting injuns, and I ain’t an injun. And I’m in morning as much as you, ’cause if this ain’t morning then I don’t know when it is, and if I ain’t in it, then I don’t know where I am.” Tom folds his arms in an angry way (being pretty nifty with his gestures), but he don’t say nothing, so I say: “Way I see it, Tom, folks die ’most every day. Maybe not in Petersburg, but then most folks ain’t in Petersburg, so I don’t claim to know for sure how they fare, but I reckon not hardly a day goes by without somebody somewheres up and dying. And if ’n it’s one of those things folks call an everyday occurrence (on account of its ’curring every day), then it don’t make no sense to go upsetting yourself outrageous, ’cause you’ll only have to go upsetting yourself all over agin the next day when the next body to die dies. And it ain’t as if Joe’s the first friend we had as went and died, is it? You ain’t forgot Jimmy Hodges as got took off by the typhus only this spring? No, you ain’t, Tom; I ’member you beating him at knucks and ring-taw and winning a whole passel of marbles off of him, white alleys and all. Sure you ’member Jimmy Hodges, don’t you, Tom?”

Huck

Huck